There wasn't much to the story, not even a date. It was passed down in a place where time didn't matter much. Here it is: Many years ago, two men went on a hunt in the bush a day and a half's walk from the nearest village, high in the mountains that thrust up above the jungle of Papua New Guinea. One night, they heard aircraft engines and then the sound of a plane smashing into the mountainside. The next day, they looked around but didn't find the wreckage.

There wasn't much to the story, not even a date. It was passed down in a place where time didn't matter much. Here it is: Many years ago, two men went on a hunt in the bush a day and a half's walk from the nearest village, high in the mountains that thrust up above the jungle of Papua New Guinea. One night, they heard aircraft engines and then the sound of a plane smashing into the mountainside. The next day, they looked around but didn't find the wreckage.

There was, of course, a precise time and date: 1:21 a.m., Nov. 5, 1943. Other tales were born at that moment, tales handed down for 60 years all across the United States. "Your Uncle Buddy was a bombardier on an airplane that went missing one night, and we still don't know what happened to him."

"Your father ..."

"Your grandfather ..."

Now the stories have an end. After more than two years of analysis and DNA testing, a Defense Department lab in Hawaii has identified remains of the nine crew members of that B-24D bomber [B-24D Liberator 42-40972]. On Wednesday, Iris Sharber Hafner Hilliard, 88, of Springmoor Retirement Center in Raleigh, will travel to Arlington National Cemetery for the burial of 1st Lt. William M. Hafner, her first husband and the pilot of the plane.

"After all this time, to know, to actually know, is something I just didn't expect," Hilliard said. "It's all I could ask for -- except for him to have come back alive."

1941: Hello, love

It was 1941, and Pasquotank County native Iris Sharber was 23 when she walked into a drugstore in Norfolk, Va. Behind the soda fountain was a good-looking engineering student named Bill Hafner.

Soon they were a pair. She was a little spontaneous, he was more serious -- a good quality in a pilot, even though he flew just little Piper Cubs then, not bombers.

Hafner wanted to finish his degree, but he loved flying and joined the U.S. Army Air Corps even before the war began. They married on the day he graduated from flight school in July 1942.

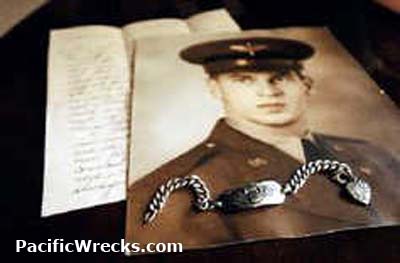

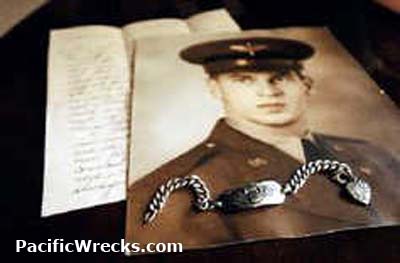

He got his own bomber and crew and, in October 1943, was assigned to the Pacific. She gave him an identification bracelet and attached to it a silver heart from her own bracelet.

"Honey, you will never know how much the identification bracelet and the little heart mean to me," Hafner wrote on Oct. 29, in one of six letters the 24-year-old sent home. "I never take them off and they are a constant reminder of you; not that I need a reminder as I think of you always."

Hafner's B-24D was fitted with crude radar and specialized in night missions. About 6 p.m. on Nov. 4, 1943, it took off from an airstrip at Dobodura on the southern end of the island for armed reconnaissance near the island of New Ireland to the northeast. A few hours later, the crew found a 10-ship Japanese convoy and was told to shadow it as long as fuel allowed.

At 12:40 a.m., as the plane returned to base, one of its radio operators called to say it had bombed the convoy, scored three direct hits and destroyed a ship. It was later determined that the crew had sunk a light cruiser -- a big prize.

At 1:20 a.m., the radio operator called the airfield and asked that a navigation signal be turned on to help it find its way home. His words were the last heard from the plane.

Nov. 5 was Hafner's birthday, and Iris was visiting his parents' house in Norfolk when a young woman walked up to the house to deliver the news that the plane was missing.

She was so shocked that she can't remember the woman's words.

"I'll never forget the way she looked, though," Hilliard said. "She was just a young girl, and I'm sure she hated to tell us, and her eyes were almost glassy."

Afterward, she did little more than work at her job in a Navy coding office and go home, telling herself that she was doing her modest part to win the war and maybe get her husband home.

In 1946, the Army declared the crew dead. Hilliard said she managed to hold two opposing beliefs, that her husband was dead and that he wasn't.

"When you don't want to believe something, maybe you halfway believe it," she said.

200 crash sites in area

New Guinea's mountains rise more than 3 miles into the sky, and they are dotted with crash sites, including about 200 from World War II that are still unfound, U.S. military experts say.

That's probably the largest concentration of such wrecks anywhere in the world, said Justin R. Taylan.

His Web site, PacificWrecks.com, tracks World War II aircraft that went down in the region.

"The crews feared the terrain there as much as they feared the enemy," Hilliard said.

Local customs regarding the wrecks are irregular. Stay away, say some people -- these are places of danger. Others loot the sites and drag in shredded aluminum to sell for recycling.

New Guinean hunters had noticed the B-24 several times over the years but gave it a wide berth until January 2002, when Robert Simau, son of one of the hunters who had heard the crash decades before, decided to go looking for the source of the story.

A couple of months later, he walked into a government office and handed over three pieces of tarnished metal. "Armacost" said one dog tag. "Eppright," said two others. Simau had also written down the tail number of the airplane.

That's when facts about the crash began trickling back to the United States, where, after six decades, crew members' parents had died, along with many brothers, sisters and wives.

Among the survivors, hardly anyone thought much about whether the crew might still be found. All those years ago, the Army said they probably crashed at sea.

The site, though, was 10,800 feet up in the mountains, in line with the curved course the plane likely would have followed to take it around the Japanese-occupied island of New Britain.

Pentagon's role

The Pentagon's Joint POW/ MIA Accounting Command is charged with finding, recovering and identifying personnel lost during and since World War II. It conducts about 25 recovery missions every year, mostly in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Its Hawaii lab identifies six to eight service members a month.

The missions are often dangerous because of issues such as rugged terrain, altitude and the frequent presence of old explosives. The first U.S.-chartered helicopter investigating the B-24 site struggled with the altitude, developed engine problems and had to turn back without landing at the site. Then, a helicopter carrying members of the first team sent to recover remains crashed, and the pilot was killed.

In August 2003, another team with 11 members arrived and hired 35 villagers to help with what would be the equivalent of an elaborate -- and potentially explosive -- archaeological dig. More than 550 square yards of soil were dug up and carefully sifted.

The team found part of an instrument panel that included a clock. The hands were stopped at 1:21 a.m., a minute after the radio operator's last call.

The recovery mission lasted more than a month. The precise locations of the scattered parts of the plane were carefully cataloged, along with bones, bits of boots and other debris.

Then the remains and personal effects were packed for the trip to Hawaii. There were rotted wallets, corroded watches and a bracelet with a small heart dangling.

Relatives, including Hafner's four nieces, were DNA tested so that bones could be matched to specific fliers.

In April, 63 years after the woman with the glazed eyes broke the news, another Army civilian employee visited Iris Hilliard. This woman came with better news --a 2-inch-thick book of reports, analysis, diagrams and photos documenting the recovery and identification of her husband's remains.

More than 78,000 service members were listed as missing during World War II, and only a few hundred have been recovered in recent decades.

Hilliard points to her own case as reason that all those families shouldn't lose hope of finding an answer.

"To know, to actually know, is something special," she said.

Recently, she got a small package in the mail. She opened it to find the bracelet and turned over the little dangling heart.

After six decades in New Guinea's soil, the words engraved on the back of the charm were still clear: "Forget Me Not."

Staff writer Jay Price.