The Nelson Flack Incident

A Failed Rescue Attempt, Daring Escape and Rediscovery of the Crash Site

by John

Douglas

February 14, 1944 Mission Over Wewak

In February 1944 the Allies in New

Guinea were fighting Japanese Forces on the ground along the Rai

Coast to the east of Madang; and in the mountains behind the Rai

Coast as well. Madang was finally occupied by Allied forces on

15th April 1944. The Ramu River valley behind Madang was in Japanese

hands throughout all of February and March 1944.

On February

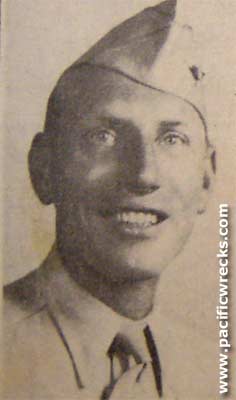

14, 1944, the 49th Fighter Group took off from Gusap Airfield to attack enemy forces at Wewak. in the Ramu/Markham Valley. The 49th Fighter Group consisted of

3 Fighter Squadrons, the 7th, 8th and 9th. Nelson Flack was a

Lieutenant in the 8th Fighter Squadrons; and that day he claimed a Ki-61 Tony shot down into the sea. Other 49th FG claims that day totaled (8 – 1

Tony and 7 Oscars). However, Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (JAAF)

records acknowledged losses (of pilots) for that day total only 2

(1 Tony and 1 Oscar). The Tony was flown by Sgt. Major Rokusaburo

Nakamura of the 68th Hiko Sentai. However, Japanese records indicate

that he was killed in a accident, not in combat.

Crash Landing

During the aerial dual Nelson Flack's

P-40N Warhawk 42-104986 was damaged. On the return from Wewak to Gusap he lost power and

was forced to put down in a kunai (grass) patch near the Ramu River,

in enemy held territory. His report indicates that as he attempted to

land in the kunai, but his plane stalled in the approach, hit a tree,

lost the propeller and, slid across the kunai before hitting a small

hill. He was knocked out by the impact. When he recovered, he found that

he had a broken arm and a severe gash on his forehead, caused by hitting

the cockpit fittings. After he escaped from his plane, he set it on fire,

to prevent it falling into Japanese hands (another version is that the

plane exploded from petrol fumes coming in contact with the hot engine).

L-5 To the Rescue, Also Crashes L-5 To the Rescue, Also Crashes

The same day a 25th

Liaison Squadron pilot Sgt.

Eugene Salternik, attempted to land

his small observation plane a Stinson

L-5 in

a nearby kunai patch, but the L-5 somersaulted on landing in the

rough, long grass. Salternik was not hurt. The 25th Liaison Squadron

had only arrived in Nadzab three days earlier and this was their first

full frontal taste of operations. It took him a further day to

reach the P-40 wreck.

Australian

Commando Parachuted To Site

Nelson

Flack had been seen to land by his colleagues and the resultant smoke

from his wreck served to provide a guide to both allies and to the enemy.

At Gusap his crash was reported to the Commanding Officer, and it was

quickly decided, due to the ruggedness of the terrain, its remoteness,

and because it was behind enemy lines; that an Australian

Commando Hector Henstridge, would parachute

into the site and help Nelson walk out. Henstridge had only flown once

before in his life, and certainly had never parachuted before. Still,

this was a time of war and emergencies call for special solutions. Hector

landed near the wreck on day 2 and found Nelson missing from the site.

He had wandered off. Nelson

Flack had been seen to land by his colleagues and the resultant smoke

from his wreck served to provide a guide to both allies and to the enemy.

At Gusap his crash was reported to the Commanding Officer, and it was

quickly decided, due to the ruggedness of the terrain, its remoteness,

and because it was behind enemy lines; that an Australian

Commando Hector Henstridge, would parachute

into the site and help Nelson walk out. Henstridge had only flown once

before in his life, and certainly had never parachuted before. Still,

this was a time of war and emergencies call for special solutions. Hector

landed near the wreck on day 2 and found Nelson missing from the site.

He had wandered off.

"Flack Field"

The three of them then set out to create

a small, landing strip near the P-40, but without tools it proved

to be quite difficult. They achieved a small partially prepared area

by the expedient of rolling their bodies in the grass. Gradually

a small strip was created. It was the custom in New Guinea at that

time by the allied airforces command to name airstrips after well

known (and usually deceased) aviators. The strip become known to

these men as "Flack Field".

Another L-5 Attempts To Land

Six days after Nelson

Flack went in, a second L-5 piloted by Sgt. James Nichols, attempted

to land at Flack Field. This rough landing he broke his propeller,

and the wheel gear struts were bent as well. 3 wrecks! The next day

a third L5 pilot – Tom

Stallone – successfully

landed at Flack Field. It was judged impractical for him to recover

anybody, so he took off successfully and returned to Gusap by himself.

Back at Gusap a decision was taken not to invest any more planes

and pilots in this particular recovery.

Trek To Rescue Themselves

The

four men now had no option but to walk out. This they did successfully,

taking 21 days in all. Their friends were able for a short period

to follow the men on their expedition to freedom but eventually lost

contact. After a few days they were declared missing in action, presumed

captured by the enemy forces present in the area. The trip out to

freedom took a real toll on all of the men, Nichols wasting away

to 90 pounds. All of their shoes rotted and Nichols had to be stretchered

the last 20 miles. After recovery and rest they all eventually returned

to duty. There is a photograph of the men when they reached Faita. It clearly shows the strain that they have been exposed

to. No smiles there. Then, the were returned to Gusap. The

four men now had no option but to walk out. This they did successfully,

taking 21 days in all. Their friends were able for a short period

to follow the men on their expedition to freedom but eventually lost

contact. After a few days they were declared missing in action, presumed

captured by the enemy forces present in the area. The trip out to

freedom took a real toll on all of the men, Nichols wasting away

to 90 pounds. All of their shoes rotted and Nichols had to be stretchered

the last 20 miles. After recovery and rest they all eventually returned

to duty. There is a photograph of the men when they reached Faita. It clearly shows the strain that they have been exposed

to. No smiles there. Then, the were returned to Gusap.

RAAF Visit Wrecks in 1946

This

is a great survival story from the war years in PNG; and there are

many other great stories as well that can be recounted. What made

this story so interesting to me was the loss of 3 planes in the same

incident. One of several follow up reports on the incident

was subsequently filed by the RAAF in 1946; when they were searching

the area; looking for the remains of missing Australian airmen. This

is a great survival story from the war years in PNG; and there are

many other great stories as well that can be recounted. What made

this story so interesting to me was the loss of 3 planes in the same

incident. One of several follow up reports on the incident

was subsequently filed by the RAAF in 1946; when they were searching

the area; looking for the remains of missing Australian airmen.

At

that time their report noted that “the tail of the

P-40 was marked in green and white checkerboard pattern, the

right side of the fin bore the numbers 986 and the left side 210.

(Flacks aircraft was P-40N Warhawk 42-104986). Although burnt around

the engine and cockpit the aircraft appeared to have made a good

crash landing. About 80 yards away is a Vultee Stinson L-5”.

The RAAF did not locate the second Stinson L-5

was a mile away (Salternik's).

Over the past 60 years a number of semi - official

histories have been written up of the combat record of the 49th Fighter

Group and also of the activities of the 25th Liaison Sq. (of the 71st

Technical Recon Group) and each of these – inevitably – deals

at some length – on

this incident. These histories are all “good yarns” but

are short on the specifics of the location, and any subsequent history

of the planes involved.

Search For The Aircraft Wrecks

I

have been interested in the war history in Papua New Guinea since

I arrived in country in 1989. This interest; sometimes a compulsion,

always a passion has taken me to many of the aircraft wrecks that

still remain in the country, nearly 60 years after the end of the

combat. I have also dived on plane and ship wrecks in the sea, interviewed

and recorded the reminisces of Papua New Guineans who recall those

times and visited battlefield sites as well. I have become an amateur

expert on these times and places and am often consulted by others

who seek information on particular circumstances from that era. I

have been interested in the war history in Papua New Guinea since

I arrived in country in 1989. This interest; sometimes a compulsion,

always a passion has taken me to many of the aircraft wrecks that

still remain in the country, nearly 60 years after the end of the

combat. I have also dived on plane and ship wrecks in the sea, interviewed

and recorded the reminisces of Papua New Guineans who recall those

times and visited battlefield sites as well. I have become an amateur

expert on these times and places and am often consulted by others

who seek information on particular circumstances from that era.

The “Flack incident” is one of about

40-50 stories that I keep an eye on. As far as I can tell from my inquiries

and research; no one had been to the site since 1946 when the RAAF

searchers visited briefly, apart from the local villagers. I have access

to, or own copies of most of the records and histories of the various

forces: American, Australian, New Zealand and Japanese. I also have

a number of lists, complied by myself and others of various wreck locations

throughout PNG that is constantly scrutinized and added to.

Flacks P-40 appeared to have been unvisited because

of its considerable remoteness. With literally thousands of wrecks

in the country there are plenty of other options for the curious

to visit should they wish to seek out plane wrecks. This wreck is

one of many that I would like to visit, but to get to it requires

helicopter time that I can normally not easily afford; so for several

years I have been waiting for the chance. That chance came in early

2004 that I was able to visit the scene of the “Flack

Incident”.

Visiting Nearby Villages

The

visit was actually made twice. The first trip was to locate the village

near where the wreck was reported in 1946 and if possible to locate

and inspect the wreckage. This goal proved somewhat optimistic. The

village had relocated itself by some three kilometers from its last reported

position and took considerable time to locate even with a helicopter. We visited three other villages in the general area

before successful in locating villagers who claimed to know of aircraft

wrecks that seemed to fit the particular description I was able to

provide. The

visit was actually made twice. The first trip was to locate the village

near where the wreck was reported in 1946 and if possible to locate

and inspect the wreckage. This goal proved somewhat optimistic. The

village had relocated itself by some three kilometers from its last reported

position and took considerable time to locate even with a helicopter. We visited three other villages in the general area

before successful in locating villagers who claimed to know of aircraft

wrecks that seemed to fit the particular description I was able to

provide.

Further discussion in pidgin with the villagers

indicated “Yes

we have three plane wrecks, but one was burnt and is of no value; all

three have only one engine each and no, they did not know what had

happened to the pilots." This all seemed to good to be true. A bit

of faith was called for. They were asked to clear a space for a helicopter

to land near the wreckage and were given a date of return. I advised

that we would be back in three weeks time.

As we left, we were given

a list of vital community needs, from school books and medicines

to a guitar and watches that we should bring on our return. It was

certainly an act of faith (or foolishness) that we committed ourselves

to return, as the planes may not have existed (villagers sometimes

give positive responses to any query), or they may not have cleared

the landing areas (the chopper couldn't’t

land in the kunai, as the grass was to long for the tail rotor) on

this first visit.

I had a few anxious moments over the next three weeks. Would it all

work out? Was my research accurate (often these records are general only

as to location, or the historic observer was not skilled at map reading);

or perhaps the wrecks been destroyed or damaged in the last 60 years.

The truth is rarely as expected or predicted. I kept these natural doubts

to myself.

Eventually the day for our return arrived. The number of curious was down

this time from 5 to 3. This gave more space for us inside on the journey. We returned to the village and landed in the

garden again. Anxious queries from me soon produced the claim that

the landing pads had been cleared and that most of the small village

population was on site (it was a good days walk away); waiting for

us. I handed the guitar and school supplies over to the “stay behinds”,

and we helicoptered off with a local guide, his first

ride in a helicopter. A few minutes flight across the dense heavy forest took us to a kunai

patch and a smudge fire. The pipe framework of a small plane was visible

in the middle of a recently burnt kunai patch. The chopper landed; I

and the guide got out, and the chopper returned for my colleagues.

L-5 Serial Number 42-98066

I inspected the wreckage. It was clearly an upside down L5, with all

that remained being the body and tail frame of piping, and an engine,

still with its cowl present The wings had disintegrated. This looked

very much like Salterniks plane, which was recorded as being capsized,

in a clearing about a mile away from the other planes. No serial numbers

were obvious. The expedition was looking good. Questioning the local people who had gathered

there for the fun and entertainment, they said the other plane wrecks

were several hours walk away, and that an area had also been cleared

at that place for the helicopter to land. After a period for photography

and contemplation, I returned to the helicopter which had now arrived

and flew to the second location. I inspected the wreckage. It was clearly an upside down L5, with all

that remained being the body and tail frame of piping, and an engine,

still with its cowl present The wings had disintegrated. This looked

very much like Salterniks plane, which was recorded as being capsized,

in a clearing about a mile away from the other planes. No serial numbers

were obvious. The expedition was looking good. Questioning the local people who had gathered

there for the fun and entertainment, they said the other plane wrecks

were several hours walk away, and that an area had also been cleared

at that place for the helicopter to land. After a period for photography

and contemplation, I returned to the helicopter which had now arrived

and flew to the second location.

This took some time as the local guide could

not initially identify the site. Eventually, after a change of guide

I arrived at a small clearing in light forest. The clearing had left

several foot high stumps which the pilot had to avoid in a very skilled

landing. I got out with two local guides and while the pilot returned

for my colleagues we tried to make the pad safer for follow up landings.

Considerable debris was removed (mainly logs and branches) and several

stumps cut down to ground level. After half an hour of frantic activity

the site was much cleaner and I could relax while waiting the chopper’s

return. I was sweating freely. As soon as I slowed down the dreaded “sweat

bees” arrived.

These bees are not toxic or poisonous, but do enjoy a good drink

of sweat in the hot humid climate that we were in. They are a local

pest – known

and dreaded throughout the Ramu Valley. In the mid morning they

were a minor pest but became a real bother as the day wore on,

with literally hundreds on my body and clothes at any one time.

L-5 "Termite" Serial Number 42-98085

On the other side of the clearing was a second pipe frame plane wreck.

This one was upright, with the wings gone (made of timber and canvas).

The landing gear was buried in the soil but the body was in much

better condition than the first wreck. It had been under forest cover

for several decades as the forest succession had replaced the kunai

and had consequently avoided the occasional grass fire that had affected

the first wreck.

The expedition was looking more and more successful.

The wrecks were exactly where the official records made them out

to be. They had been practically undisturbed. I had not yet seen

the P-40 wreck, but I felt relief that my research proved I had been

accurate as to description and to location (at least for the two

L5s). I also felt excitement and pleasure that goes with such adventures

of effort and success; of anticipation fulfilled.

The

helicopter returned with my companions and after some maneuvering

made a successful landing. It was a long way to walk out, and we

didn’t

want to repeat the trials of the airmen of 1944. My companions were

anxious to see the P-40, and the guides told us it was a short

walk through the forest. The forest appeared to have grown up since

the war years and consisted mainly of light trees, no more than

50-60’ high, with a leaf

covered forest floor, which made walking easy.

P-40N Warhawk Serial Number 42-104986

Subsequent research

has revealed that Sgt. Stallone died in New Guinea during the War

whilst the rest survived. Nelson Flack was killed in Korea. Both Sgt. Nelson and Lt. Hestridge have since departed this

life, but Eugene

Salternik is a sporty 92 year old living in Southern

California. Subsequent research

has revealed that Sgt. Stallone died in New Guinea during the War

whilst the rest survived. Nelson Flack was killed in Korea. Both Sgt. Nelson and Lt. Hestridge have since departed this

life, but Eugene

Salternik is a sporty 92 year old living in Southern

California.

References

Eugene

Salternik interview

Additional research by Justin Taylan and Phil

Bradley

Ghost

Wings Magazine Issue 12 "Skeletons in the Grass - An Epic WWII

Rescue" by John Douglas & Justin Taylan

Contribute Information

Do you have photos or additional information to add?

|