|

|

|

|

| Missing In Action (MIA) | Prisoners Of War (POW) | Unexploded Ordnance (UXO) |

| Chronology | Locations | Aircraft | Ships | Submit Info | How You Can Help | Donate |

|

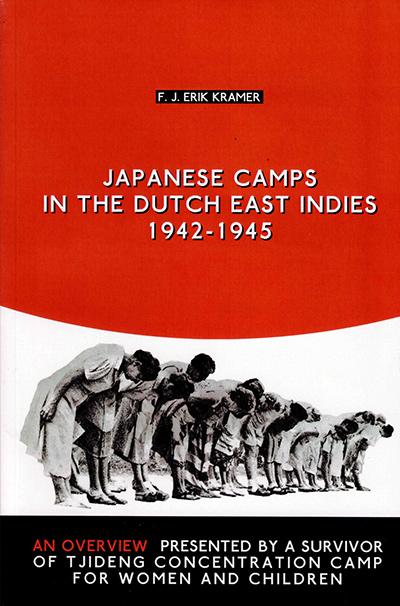

by F. J. Erik Kramer FEK 2011 Softcover 52 pages photos, illustrations, maps ISBN: N/A Cover Price: N/A Language: English Return to |

Japanese Camps in the Dutch East Indies 1942–1945 An Overview Presented By A Survivor of Tjideng Concentration Camp For Women and Children This book was written and self-published by Frans Johan Erik Kramer about his experiences as a child detainee in the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) during the Pacific War. The author describes the book as "I discuss my own experience, as a child imprisoned by the Japanese Empire, together with a broader historic overview, and supported by historic documents and illustrations." F. J. Erik Kramer was born August 26, 1936 in Batavia (Jakarta) on Java in the Netherlands East Indies (Indonesia). His father, Frans Kramer was Chairman of the General Agricultural Syndicate who became the head of the underground resistance in western Java until betrayed, arrested by the Imperial Japanese Army Kempeitai (Military Police). When he refused to cooperate, he was tortured and died July 21, 1943. Posthumously, the Queen of Netherlands bestowed the Verzetsster Oost-Azië (VOA), the Resistance Star East Asia. He is buried at Jakarta (Ancol) Netherlands War Cemetery at row V grave 157. On March 8, 1942 the Dutch unconditionally surrendered the entire Netherlands East Indies (NEI) to Japan. Immediately, Dutch citizens were interned in more than 530 concentration camps for Prisoners Of War (POWs) and civilians, including 80 camps on Java. Dutch women and children were segregated from men and detained in separate camps with boys older than ten years old sent to camps for men or to special boys only camps. Initially, their captivity was managed by Japanese civilian staff and conditions were bearable. Next, the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) took over administration and operation of the camps and the situation deteriorated for the detainees. Meanwhile, all Dutch assets were confiscated and transfered to Japan including any private wealth and household possessions left behind. At age 6, F. J. Erik Kramer recalls how a Japanese car pulled up to his house and his mother, Francijna and sister Tineke were ordered to be ready to leave in an hour with only whatever bagged they could carry. The rest of their possessions were to be left behind and confiscated by the Japanese. At age six, he remained with his mother and were sent to Camp Tjideng (Cideng) a low income area of Batavia where roughly 3,000 other Dutch women and children were interned. They were neglected and slowly starved as part of a deliberate effort to eliminate all foreigners and Dutch influence in the East Indies. Living in single family homes overcrowded with between 25-40 individuals without any privacy and were forced to share a single toilet and shower. Every prisoner was assigned a number tag was to be worn at all times and be present for roll call twice a day. The prisoners, including children were required to bow to any Japanese. If they forgot or their bow was not low enough, they were beaten. The only food provided was in the afternoon in the form of unusable remainders from a nearby market including much that was spoiled or unfit for consumption. Teenage girls were given the task of preparing meals by boiling the food in metal drums to make a soup and meals were estimated to have only 500-600 calories causing weight loss, starvation and disease. Only once were a limited number Red Cross parcels distributed, but they had been looted by the Japanese and were shared by six people. They were never provided any medicine and disease was rampant. No religious services were allowed and children were not allowed to attend school or have any educational instruction. By 1945, the death rate at Camp Tjideng reached 22% with one out of every five inmates died and prisoners. In fact, the percentage was higher as sick individuals were removed from the camp to nearby Sint-Vincentius church to die alone and were not counted in the official camp statistics. After nearly three years in captivity, if the Pacific War not ended in August 1945, the Red Cross estimated everyone left in the camp would have died in six months or less. On August 1, 1944 a Japanese War Ministry policy memorandum dubbed the "Order To Kill" was issued allowing internment camps to kill any remaining prisoners by any means on August 26, 1945. After the surrender of Japan on August 15, 1945 the internees at Camp Tjideng were not notified the Pacific War had ended for another week. In early September 1945, British Army soldiers arrived in Java and discovered the deplorable internment camps across Java. Ironically, they commanded the Japanese Army to defend the camp from Indonesian agitators that began rioting for independence and threatened the Dutch that survived captivity. In 1946, commandant of Camp Tjideng, Lt. Kenichi Sonei was put on trial as a war criminal, found guilty and executed. Postwar, the Dutch victims experienced post-traumatic stress dubbed "Post Concentration Camp Syndrome" and many were treated at a clinic established in the Netherlands. Many of the survivors felt they never received justice and formed a Netherlands based association that sough from the Japanese government: 1) acknowledgment of wrongdoing against innocent men, women and children 2) a formal apology and 3) token financial compensation. To date, Japan has not acknowledge these grievances. Postwar, nine year old F. J. Erik Kramer was repatriated to the Netherlands. Although his mother survived captivity, she died soon afterwards as a result of years of detention. Kramer graduated from Erasmus University and became a consultant for the airline industry, worked for Venezolana Internacional de Aviación Sociedad Anónima (VIASA) then as a consultant for other airlines and retired to West Melbourne, Florida and was a volunteer at Valiant Air Command Warbird Museum and originally wrote the book as a presentation for the museum to educate people about the Japanese atrocities against civilians and children that he personally experienced. F. J. Erik Kramer passed away August 11, 2022 at age 85. Review by Justin Taylan Return to Book Reviews | Add a review or submit for review |

| Discussion Forum | Daily Updates | Reviews | Museums | Interviews & Oral Histories |

|