Speak about your connections to World War II and how this sparked your interests.

Three members of my family went to the Pacific in World War II; only one came back, and he never spoke about it. Of the two who died, 1st Lt. Philip E. Wood Jr. was the family hero. He was my grandmother's cousin – extremely intelligent and erudite – very much Destined For Greatness. He was also the last person one would expect to volunteer for the Marine Corps, let alone pass all the requirements to become a combat officer, and a well-respected one. His death on Saipan at the age of 23 left a major scar on that generation; he was not talked about so much as invoked. They were proud of him – he died trying to rescue a group of civilians, and was decorated for the attempt – but never stopped being an immediate loss.

Three members of my family went to the Pacific in World War II; only one came back, and he never spoke about it. Of the two who died, 1st Lt. Philip E. Wood Jr. was the family hero. He was my grandmother's cousin – extremely intelligent and erudite – very much Destined For Greatness. He was also the last person one would expect to volunteer for the Marine Corps, let alone pass all the requirements to become a combat officer, and a well-respected one. His death on Saipan at the age of 23 left a major scar on that generation; he was not talked about so much as invoked. They were proud of him – he died trying to rescue a group of civilians, and was decorated for the attempt – but never stopped being an immediate loss.

Luckily for me, Phil was a great letter writer. I got a typed copy of about fifteen letters when I was in college, and they struck an immediate chord. I was 22 at the time – the same age he was – and he was writing, in part, to his younger sister Gretchen, who happens to be my younger sister's namesake. It was hard not to feel a personal connection. I decided I wanted to learn as much about him – and by extension, his unit and the men he served with – as humanly possible. Within a week I was in touch with two members of his old company. That's when WWII research stopped being a casual interest.

My first history website is First Battalion, 24th Marines – that was my first foray into presenting research online and building connections with veterans and their families. It's strictly a unit history, delving into personal stories and aligning them with official histories and documents to tell a detailed story of a little-known Marine battalion. The long reads about the battles are becoming the focal point.

My first history website is First Battalion, 24th Marines – that was my first foray into presenting research online and building connections with veterans and their families. It's strictly a unit history, delving into personal stories and aligning them with official histories and documents to tell a detailed story of a little-known Marine battalion. The long reads about the battles are becoming the focal point.

How did you become interested in World War II and casualty research?

I started out as a Titanic geek. My dad knew some people at Wood's Hole; I got to "interview" Dr. Robert Ballard in 1992 or 1993. I was eight and totally star-struck, so my dad had to ask all the questions. Dr. Ballard was very patient and kind, he even complimented me on a little report I’d done on the disaster. He must have been working on Lost Ships of Guadalcanal at the time – a year or two later, I bought the book and learned that he'd found my great-grand-uncle LCDR Edmund Billings cruiser, the USS Quincy (CA-39). That made a huge impression on me, because he went down with the ship. Ballard even had an account of his last moments. Heroic stuff: emerging from the blazing superstructure, declaring "don't worry, the ship will go down fighting." That's not what captivated me, though: it was that half his face was gone, he was literally looking at death, and I wondered what was really going through his mind in those last moments before he collapsed on the deck.

I started out as a Titanic geek. My dad knew some people at Wood's Hole; I got to "interview" Dr. Robert Ballard in 1992 or 1993. I was eight and totally star-struck, so my dad had to ask all the questions. Dr. Ballard was very patient and kind, he even complimented me on a little report I’d done on the disaster. He must have been working on Lost Ships of Guadalcanal at the time – a year or two later, I bought the book and learned that he'd found my great-grand-uncle LCDR Edmund Billings cruiser, the USS Quincy (CA-39). That made a huge impression on me, because he went down with the ship. Ballard even had an account of his last moments. Heroic stuff: emerging from the blazing superstructure, declaring "don't worry, the ship will go down fighting." That's not what captivated me, though: it was that half his face was gone, he was literally looking at death, and I wondered what was really going through his mind in those last moments before he collapsed on the deck.

World War II had its hooks in me, though, and while I spent a lot of time on the American Civil War, I kept gravitating back to the Pacific Theater of Operations (PTO). After years of reading and researching it seemed logical to try graduate school and see if I could make my interest something more than a hobby. The casualty experience is fascinating because it's impossible to understand in the abstract; it has to be experienced, and luckily most of us will never experience this particular trauma. James Jones put it really well in The Thin Red Line:

"They had crossed a strange line; they had become wounded men; and everybody realized, including themselves, dimly, that they were now different. Of itself, the shocking physical experience of the explosion, which had damaged them and killed those others, had been almost identically the same for them as for those other ones who had gone on with it and died. The only difference was that now these, unexpectedly and illogically, found themselves alive again."

There's something particularly poignant about the fate of the missing, many of whom faced this final trauma all alone without the assurance that their body would even be brought home.

What attracted you to the topic of Missing U.S. Marines from World War II?

His name was (is) Sergeant Arthur B. Ervin, Jr.; he was a 22-year-old sergeant from a little town in Texas, and he gave up his life on Saipan while trying to rescue his platoon leader – my ancestor, 1st Lt. Philip E. Wood Jr.

His name was (is) Sergeant Arthur B. Ervin, Jr.; he was a 22-year-old sergeant from a little town in Texas, and he gave up his life on Saipan while trying to rescue his platoon leader – my ancestor, 1st Lt. Philip E. Wood Jr.

Eyewitness accounts said they died together. A letter from their skipper said they were buried together. Yet I learned in 2010 that Sgt. Ervin was on the list of unaccounted-for Marines. That didn't make sense, so I thought I'd investigate a bit. The story that came out was so involving – I'm still learning more about this guy to this day – it drove home the fact that behind every name on the casualty list, there's a whole life story. There's personality. You think, they died so young they never had a chance to live – but they all had intricate histories, however brief.

Of course, that applies to all missing from all wars, and that's a ton of stories. I figured I'd be better off doing one thing and doing it well, so USMC losses in WW2 are my specialty. I'll research anything, though, it's all fascinating.

Ervin, by the way, is still unaccounted for. I could tell you, with a high degree of certainty, exactly where he's buried, and I'm not the only one, but getting official movement on it is… Well, let's leave it at frustrating.

Explain how you use historical records in your research.

Well – my experience with the Arthur B. Ervin, Jr. case and a few others leads me to believe that there are plenty of clues still hidden in firsthand accounts and historical documents. We have the benefit of seventy-plus years of additional research, veteran's testimony, archaeological findings, and historiography – all of these help fill in the gaps, explain the omissions, and clarify the inaccuracies that hindered the original search parties.

It's easy to get lost in all the minutiae and tempting to place yourself in the midst of what you're reading… but of course, the reality is making a ton of spreadsheets. Getting all your pertinent information into one searchable format is essential. I spend a ton of time in color-coded Google sheets. Laying information out in a visually accessible way can be a tremendous help. For Leaving Mac Behind, I created a searchable grid of the cemeteries on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Gavutu based on original burial records; I found a lot of conflicting information in those records that I would have completely missed otherwise.

Another data visualization exercise led to mapping the home addresses of the casualties – I've done them for Guadalcanal and for Tarawa, and it's interesting to see where these guys lived in relation to each other; who were neighbors or possibly classmates or hometown friends. As an example, I found two guys from Riverside, New Jersey – Robert M. Eastburn and Matthew J. Kirchner – who grew up two blocks from each other. They were the same age, so in the same class at school. Both served with C/1/5th Marines; both died at the Matanikau River on 1 November 1942, and both are still buried on Guadalcanal. It's hard not to imagine a backstory there.

Another data visualization exercise led to mapping the home addresses of the casualties – I've done them for Guadalcanal and for Tarawa, and it's interesting to see where these guys lived in relation to each other; who were neighbors or possibly classmates or hometown friends. As an example, I found two guys from Riverside, New Jersey – Robert M. Eastburn and Matthew J. Kirchner – who grew up two blocks from each other. They were the same age, so in the same class at school. Both served with C/1/5th Marines; both died at the Matanikau River on 1 November 1942, and both are still buried on Guadalcanal. It's hard not to imagine a backstory there.

References

Missing Marines – Map: The Cost Of Tarawa

Missing Marines – Map: The Cost Of Guadalcanal

Tell about your website Missing Marines.com and the objectives.

Missing Marines.com was supposed to be a storytelling site; then it was supposed to be a breaking-news-in-the-recovery-world site. Now it's a little bit of both, with essays and photography and long biographies… anything of relevant interest. It mainly serves two purposes: increase awareness and conversation around Missing In Action (MIA) recovery efforts in general, and as a passive information collector. People Google their relatives, find their name, and send me emails with inquiries or information. We all end up learning something new.

Missing Marines.com was supposed to be a storytelling site; then it was supposed to be a breaking-news-in-the-recovery-world site. Now it's a little bit of both, with essays and photography and long biographies… anything of relevant interest. It mainly serves two purposes: increase awareness and conversation around Missing In Action (MIA) recovery efforts in general, and as a passive information collector. People Google their relatives, find their name, and send me emails with inquiries or information. We all end up learning something new.

Hopefully the audience enjoys reading it as much as I enjoy putting it together. One of the articles about Marine pilot 2nd Lt. Elwood R. Bailey received the 2019 Marine Corps Heritage Foundation General Roy S. Geiger Award, which was a surprise – mostly traffic is pretty modest. It's a niche interest.

Hopefully the audience enjoys reading it as much as I enjoy putting it together. One of the articles about Marine pilot 2nd Lt. Elwood R. Bailey received the 2019 Marine Corps Heritage Foundation General Roy S. Geiger Award, which was a surprise – mostly traffic is pretty modest. It's a niche interest.

Speak about some of the people your research has impacted or helped.

I'll never forget the first time I attended the burial of a Tarawa Marine. Jack F. Prince, a 19-year-old kid from Bellerose, New York, killed on the first day of his first battle. He was one of the guys found by Mark Noah's History Flight in Cemetery 27 on Betio. The service was all very solemn and impressive, but what really got to me was his family. None of them knew him in life, but they all grew up hearing stories about him and seeing his picture. It felt like a family reunion, and the one member who'd never been able to attend was finally there. Jack was restored to his family; he was finally home, and this long-buried trauma was finally healed.

I'll never forget the first time I attended the burial of a Tarawa Marine. Jack F. Prince, a 19-year-old kid from Bellerose, New York, killed on the first day of his first battle. He was one of the guys found by Mark Noah's History Flight in Cemetery 27 on Betio. The service was all very solemn and impressive, but what really got to me was his family. None of them knew him in life, but they all grew up hearing stories about him and seeing his picture. It felt like a family reunion, and the one member who'd never been able to attend was finally there. Jack was restored to his family; he was finally home, and this long-buried trauma was finally healed.

That really drove home an important point for me. You don't research the dead for the sake of the dead. You don't work on these mysteries for your own pride or intellectual thrill (although there is some of that, to be sure). You do it for the families who have waited so long, even if they never knew they were waiting.

What’s next for MissingMarines.com, profile every MIA Marine?

That would be the dream, yeah – have a detailed, illustrated biography of every man, with all their vitals and the information a researcher would need to start their own investigation. Realistically, though, I've been working on the website since 7 December 2011 and I'm only up to October 1943! The amount of research that goes into full bios is prohibitive for one person who has to go to work, pay bills, raise a family and sleep sometimes.

So, I'm settling for basic info on everyone, as many photos and articles as I can find, and a brief description of the action where they died. At this rate, I'll have plenty of time to work on it in retirement (which is still 30+ years down the line). Unless someone wants to create a research grant, I wouldn't say no to that.

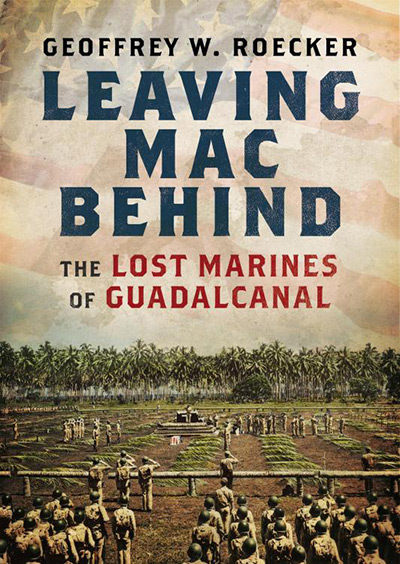

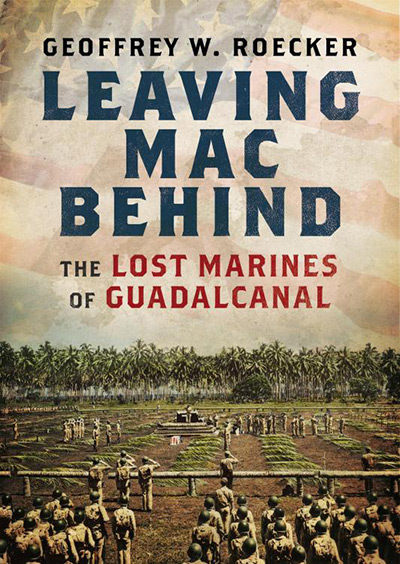

Talk about your book Leaving Mac Behind: The Lost Marines of Guadalcanal. Congratulations, the first edition is largely sold out with copies still available via Barns & Noble and Amazon Kindle version.

I wrote my graduate thesis on Guadalcanal, specifically focusing on how the Marine Corps prepared (or failed to prepare) for a battle which would turn out to be unique in their history. The main thrust was about the underappreciated role of combat intelligence (for example, the Goettge Patrol, none of whom have been recovered), but in the course of research I came to understand that there was no such thing as Graves Registration in the Marine Corps at the time. A great article by Christopher J. Martin, "The Aftermath of Hell," got the ball rolling. I wanted to see how the Marines adapted to the situation – how did they retrieve and identify their dead? How did they organize their cemeteries, from oversight to digging the holes? How did they map isolated burials, knowing how problematic the maps were? And most importantly, how successful were they in accounting for their dead? Everybody was doing this for the first time.

I wrote my graduate thesis on Guadalcanal, specifically focusing on how the Marine Corps prepared (or failed to prepare) for a battle which would turn out to be unique in their history. The main thrust was about the underappreciated role of combat intelligence (for example, the Goettge Patrol, none of whom have been recovered), but in the course of research I came to understand that there was no such thing as Graves Registration in the Marine Corps at the time. A great article by Christopher J. Martin, "The Aftermath of Hell," got the ball rolling. I wanted to see how the Marines adapted to the situation – how did they retrieve and identify their dead? How did they organize their cemeteries, from oversight to digging the holes? How did they map isolated burials, knowing how problematic the maps were? And most importantly, how successful were they in accounting for their dead? Everybody was doing this for the first time.

I expected to find an utter disaster, but instead I found that the improvised systems worked quite well – and what they learned on the 'Canal was eventually taught to the first in-theater Marine Marine Graves Registration Service (GRS) units starting in 1943.

Still, there are hundreds of American servicemen who have not been recovered from Guadalcanal. Most of them are likely still buried in isolated graves out in the boondocks. There's a whole post-war history of searching for these guys, and they're still being found to this day. I'm hoping the stories told in the book will help inspire additional efforts.

Tell about the book's focus on each loss, cemeteries and burial grounds.

Almost every memoir or oral history of Guadalcanal mentions the cemeteries; they were very visible, servicemen would visit them throughout the war. Yet there's very little in any history book, at least that I've seen, that goes into the details of how they came to be. Original records are also vague – obviously, the 1st Marine Division knew men would be killed, but they had many more pressing matters to worry about, like staying alive and able to fight. So, naturally, Graves Registration is a less-told story.

Almost every memoir or oral history of Guadalcanal mentions the cemeteries; they were very visible, servicemen would visit them throughout the war. Yet there's very little in any history book, at least that I've seen, that goes into the details of how they came to be. Original records are also vague – obviously, the 1st Marine Division knew men would be killed, but they had many more pressing matters to worry about, like staying alive and able to fight. So, naturally, Graves Registration is a less-told story.

The chaplains were the logical choice to take on responsibility for establishing the cemeteries, and it seems like they did so without waiting to be told. W. Wyeth Willard and Father James Fitzgerald set up the burial grounds on Gavutu and Tulagi, and Chaplain Charles Dittmar did the same on Guadalcanal. It was rather informal, at first – reverential, of course, but markers were literally made of scrap wood or sticks tied together. And at first, that was all it needed to be. Guadalcanal was supposed to be a short one for the Marines; they were going to take the airfield, let the Army take over, and move on to the next objective. That was the SOP they'd spent the 1930s practicing. Once the Army came along, cemetery administration would fall under the auspices of the Quartermaster, which is one of their traditional duties.

The chaplains were the logical choice to take on responsibility for establishing the cemeteries, and it seems like they did so without waiting to be told. W. Wyeth Willard and Father James Fitzgerald set up the burial grounds on Gavutu and Tulagi, and Chaplain Charles Dittmar did the same on Guadalcanal. It was rather informal, at first – reverential, of course, but markers were literally made of scrap wood or sticks tied together. And at first, that was all it needed to be. Guadalcanal was supposed to be a short one for the Marines; they were going to take the airfield, let the Army take over, and move on to the next objective. That was the SOP they'd spent the 1930s practicing. Once the Army came along, cemetery administration would fall under the auspices of the Quartermaster, which is one of their traditional duties.

Of course, it took a bit longer, and the casualties were quite a bit higher, than anticipated. It was right after the battle of Edson's Ridge that Marine HQ got serious about admin for their main cemetery and appointed Captain Richard Tonis as the first Marine GRS officer in the area. He didn't have any experience – he was a peacetime cop – but he was smart, he could order people around, and he knew how to take fingerprints which was essential when a body turned up without identification.

Tonis ran the show until the Army arrived; they appointed a quartermaster officer, Lt. Panosian, for a while, and eventually replaced him with Warrant Officer Chester Goodwin. Goodwin arrived on Guadalcanal as a field artillery corporal – but he'd worked as a mortician before the war. That made him the most qualified man in the theater. And he turned out to be an outstanding choice. The Army did a bang-up job of recovering their field burials; there are perhaps less than 100 unaccounted-for Army ground losses on Guadalcanal.

One of the things I found most striking about the Guadalcanal Cemetery is the little personal touches that men added to their buddies' graves. Poems, carvings, mementoes, weaponry; some built fences or gardens, stuck airplane propellers or artillery shells in the ground; there were countless little epitaphs and memorials and bits of doggerel that all came from the heart. All these expressions of appreciation and sorrow and love for the deceased. It makes you realize how hard it must have been to have to bury your friend in the field, or leave him unburied. Men risked a lot to retrieve fallen friends, and some who failed were deeply troubled by it for the rest of their lives.

One of the things I found most striking about the Guadalcanal Cemetery is the little personal touches that men added to their buddies' graves. Poems, carvings, mementoes, weaponry; some built fences or gardens, stuck airplane propellers or artillery shells in the ground; there were countless little epitaphs and memorials and bits of doggerel that all came from the heart. All these expressions of appreciation and sorrow and love for the deceased. It makes you realize how hard it must have been to have to bury your friend in the field, or leave him unburied. Men risked a lot to retrieve fallen friends, and some who failed were deeply troubled by it for the rest of their lives.

I wanted to add a little bit to the memorials for those guys who are still out in the jungle.

Speak about some of the people you collaborate with worldwide related to this work.

Well, that Justin Taylan fellow from Pacific Wrecks is pretty solid, I can tell you that much. I didn't really realize the importance of connections when I first got started; I was used to working on my own, but now have built up a pretty good network of colleagues and fellow researchers. Being able to email or call a colleague who can answer a question or has the file you need on a portable drive from years ago is priceless. Archival research isn't exactly intuitive, and I haven't been able to travel the Pacific islands, so knowing people who have expertise in those areas is essential. I couldn't possibly name everyone who's helped out in some way, but Katie Rasdorf, Kurt Heite, Jennifer Morrison, Dave Holland and Peter Flahavin are my go-to collaborators.

Well, that Justin Taylan fellow from Pacific Wrecks is pretty solid, I can tell you that much. I didn't really realize the importance of connections when I first got started; I was used to working on my own, but now have built up a pretty good network of colleagues and fellow researchers. Being able to email or call a colleague who can answer a question or has the file you need on a portable drive from years ago is priceless. Archival research isn't exactly intuitive, and I haven't been able to travel the Pacific islands, so knowing people who have expertise in those areas is essential. I couldn't possibly name everyone who's helped out in some way, but Katie Rasdorf, Kurt Heite, Jennifer Morrison, Dave Holland and Peter Flahavin are my go-to collaborators.

Does your work prove historical research can help solve MIA Cases?

I hope it proves that some of these cases are worth a second look – from government agencies and private researchers alike. When I first started out, Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) was the ruling entity, and they did not want any outside help. Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) is much more welcoming, in part thanks to the work of groups like History Flight, and I think their success rate shows just how much of an impact that has had.

I hope it proves that some of these cases are worth a second look – from government agencies and private researchers alike. When I first started out, Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) was the ruling entity, and they did not want any outside help. Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) is much more welcoming, in part thanks to the work of groups like History Flight, and I think their success rate shows just how much of an impact that has had.

Obviously, nothing can be solved by research alone. One of the toughest lessons to learn, and one that I'm reminded of frequently, is that the original source material can be vague, incomplete, contradictory, or simply wrong. As a historian, your instinct is to get those primary sources – and they're probably the most accurate sources available – but if you think a casualty card or Individual Deceased Personnel File (IDPF) is going to hold all the answers, you're bound to be disappointed! Often the original scribes were just as stumped in the 1940s as we are today.

What I find most interesting about MIA cases is the social history aspect. When the official records fall short, you have to fill in the gaps as best you can: that means going to oral histories, veteran memoirs, or interviewing survivors. You'll find any number of little clues from these sources. Sure, memory is imperfect; you have to try and distinguish the moments of truth from false memories or straight-up war stories, and it's not easy. However, I've found that the smaller the detail, the more truthful it tends to be. A vet might not remember the exact date that their buddy disappeared, or where on the battlefield they were – but they might remember that he was on outpost duty, or running a message to battalion, or that they saw him go down wounded or the corpsmen carrying him away. Those moments meant more, and they've been remembered for that reason.

These are decades-old cold cases, and if they were easy to solve, someone would have done it by now. It's up to us to put in the work and get these guys home. We owe them that much.

Thank you for the interview, Mr. Roecker!

Missing Marines.com

Missing Marines.com