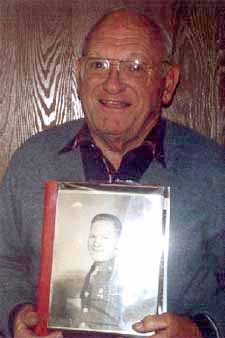

In memory

Walter Seale passed away on March 10,

2002

Seale's daughter adds: "He was very proud of his country and WWII service. As a

recessional at the funeral, his wish was to play "America the Beautiful". He lived in Clifton Park, NY with his wife. He has attended 871st reunions

in 1949, 1966, and then every one until 2002."

Overseas

Overseas

I volunteered for the Army on October 6, l942

and was sent to Fort Leonard Wood, MO for basic training in the

29th Engineer Training Bn., Co. A. About New Years of 1943 I

was transferred to H & S Co., 87lst Airborne Engineer Bn., at

Westover Field, MA. Westover is near Holyoke and it is now a

National Guard Base. We trained on how to maintain our equipment

and how to load it in C-47's and in gliders. It was winter and

we thought we were being trained for Alaska!

When we landed in New Guinea we had wool clothes.

We were sent to Camp Stoneman, CA and left Oakland on April 30, 1943 aboard USS President Johnson. America was very short

of shipping. The construction plate on the Johnson noted that

she was built in Newport News VA in 1904. She was very slow and

broke down a couple of times. In

addition to the 871st Airborne Engineers, on board were the ground echelon of the 500th

Bomb Group and the 565th Signal Air Warning (Radar) Bn. We were thirty one days enroute to Australia.

We made landfall at Townsville and then went to Brisbane for repairs to the ship. About a week later we sailed again and

arrived at Port Moresby,

Papua New Guinea a couple of days after that.

Port

Moresby, New Guinea

At Port Moresby we uncrated our equipment

at the 27th Air Depot and camped at the 17

Mile Drome (Schwimmer). We stayed at Moresby until July working

on an assortment of construction work at the air depot.

An Airborne Engineer Battalion consisted of 501

enlisted men and 29 officers. (I remember that exactly because

I typed it every day on the QM ration report) Originally there

were ten battalions, some at Westover, some at Bradley Field and

some at a field in Missouri (perhaps the name was Wakeman?).

The battalions were originally numbered from 871 to 880. All

of the equipment we had would fit into a C-47 or a glider and

was limited in weight to about 4500 pounds.

Our first mission was up to Tsilli-Tsilli in the Markham Valley. We were to build a dirt runway as

an emergency fighter landing strip . All of the 87lst and all

of our equipment was flown over the passes in the Owen Stanley

Mountains. This was wild, uncharted, territory. The C-47s of

that era were not equipped with sophisticated navigational instruments

so they flew only in clear weather. They just cleared the mountain

passes by a little bit but they got us there.

Tsilli-Tsilli

During most of the Tsilli Tsilli operation

I was left in Moresby with the rear echelon to air ship the supplies

of food, fuel and engineer materials needed on the job. Our section

alternated first on the rear echelon and then to the forward echelon.

I got to fly over to Tsilli almost every day on the near-last

plane load to get instruction for the following day.

The Australian 7th Division was holding the area

and the Japanese were on the other side of the hills at Saidor and Wewak. For a while the 5th Air Force command was afraid if

the area fell to the Japanese it would be the butt of joke and

propaganda because Tsilli Tsilli is pronounced silly - silly.

They used the name Marilinan instead.

The first thing the 871st did there was

to mow a fake airstrip nearby. This was to fool the Japanese

and make it appear like the base was bigger. In reality it was

only mowed kunia grass. The 87lst was bombed on August 15th.

Captain Kieth Munro, our chaplain, was killed.

Australians - Bully Beef &

Tea

The Australian 7th Division was a

tough lot. They had been in Lebanon, Greece and North Africa

before being sent back "home" to protect their homeland in 1942.

They lived in foxholes and under two-man shelter tents. They

were armed almost entirely with Enfield rifles that looked like

WW I issue. They had little or no equipment. They walked! Every

day they ate bully beef, hard tack biscuits and drank tea.. That

was the menu. Often we would trade with them. We had some things

we didn't always use up or need, such as dehydrated potatoes and

canned beef stew that we called coagulated transmission fluid.

I still have an Aussie hat insignia and a division shoulder patch

they I got in a trade.

On the subject of food -

the army food was not good, the air corp food was better and the Navy was the

best. We always tried to trade for better rations.

Dirt Strip

for Emergencies and P-39's

The 871st worked 24 hours a day building,

expanding and repairing at Tsilli Tsilli. The first thing they

did was make a rough dirt runway so that any strays or cripples

could make emergency landings. We got P-40s, B-25s and P-39s

that had been hit or had fuel problems. The air corps mechanics

would fix them up so that they could get back to their home base.

We worked on finishing the dirt runway and some hardstands for

parking planes. It soon became fighter base for P-39s from the

8th Fighter Squadron. The P-39s were being phased out at about

this time in favor of P-47s an P-38s but the P-39s had a cannon

in the nose and were good for strafing. As I remember, we did

not leave any wrecks or junk there. The field was later abandoned

when Gusap was developed.

The 871st worked 24 hours a day building,

expanding and repairing at Tsilli Tsilli. The first thing they

did was make a rough dirt runway so that any strays or cripples

could make emergency landings. We got P-40s, B-25s and P-39s

that had been hit or had fuel problems. The air corps mechanics

would fix them up so that they could get back to their home base.

We worked on finishing the dirt runway and some hardstands for

parking planes. It soon became fighter base for P-39s from the

8th Fighter Squadron. The P-39s were being phased out at about

this time in favor of P-47s an P-38s but the P-39s had a cannon

in the nose and were good for strafing. As I remember, we did

not leave any wrecks or junk there. The field was later abandoned

when Gusap was developed.

Nadzab

Nadzab

On September 7th we had a new assignment to build

the airfield at Nadzab,

above Lae in the Markham Valley. Two days before on the

5th, paratroopers had assaulted the area. The road to Lae was

not operable, because there was a big swamp between Nadzab and

Lae.

I remember there was a German building

at Nadzab, either a mission or school. The blackboard had writing in German, and

the date on the board, the day of our attack. I guess they had been evacuated

that day by the Japanese, and left everything the way it was. I was in the "forward echelon" sent

out ahead to Nadzab. The other part of our unit was behind, and

coordinated sending equipment forward. At Nadzab, we first built

a dirt Runway. By this time, our equipment was pretty well beat

up from constant use. The only relief came from heavy caterpillar

equipment.

There was a gold mine at Wau from the 1930s. There was another at Dobodura.

The Australian mining operators flew in their equipment in Ford

Tri-motors. They disassembled the equipment into small enough

pieces to load into the planes with a gin pole and then would

unload and re-assemble it at the site. They were expert at this.

Our supply line fund some Caterpillar D-4 model tractors and these

were disassembled into pieces and flown to Nadzab where they were

reassembled and used to supplement and replace some of the worn

out airborne equipment. Our mechanics also used the same procedure

on four-yard scrapers and 6 by 6 GI trucks. It took five plane

loads for a D-4 and three loads for a truck. It was a lot of

work, and probably very costly, but it worked.

All our equipment would fit into C-47's. For example,

it would take five C-47 to bring one of our 'dozers: 1st carried

the engine, 2nd, the tracks, 3rd the motor, 4th the final drive,

5th the blade, five planes in all! We also figured out how to send the 2 1/2 ton

deuce & half type truck. We would send one with a canvas cab,

cut the frame in half behind cab. Add a dolly wheel under front

end, put that in one plane. Take frame body in the second, and

Send the tires in a third. Three planes in all.

All our equipment would fit into C-47's. For example,

it would take five C-47 to bring one of our 'dozers: 1st carried

the engine, 2nd, the tracks, 3rd the motor, 4th the final drive,

5th the blade, five planes in all! We also figured out how to send the 2 1/2 ton

deuce & half type truck. We would send one with a canvas cab,

cut the frame in half behind cab. Add a dolly wheel under front

end, put that in one plane. Take frame body in the second, and

Send the tires in a third. Three planes in all.

Gusap

While we were at Nadzab, doing rather routine

earth moving and grading, the Australian 9th Division landed

north of Lae and the US Army (I think the 41st Div) moved up from

the south until the Allied forces controlled the area. A road

was pushed through the swamp, by US engineers who had landed at

Lae, to connect with the Nadzab site. We were relieved and our

next move was to Gusap,

northwest of Nadzab. The airborne equipment was flown, as in

the past. Rather than disassemble and reassemble the trucks and

the D-4s it was decided to convoy them overland. The area was

without roads.

The convoy was for a considerable distance.

I seem to recall that it was about fifty miles. Without roads,

the convoy had to break a trail through the kunai grass, find

places to ford the streams, excavate fording ramps, get across

the stream and then winch all their equipment across. It took

ten days or two weeks, or so. We lost one man, Cpl Heacock, a

Medic, who drowned in a swollen stream.

At Gusap we, again, quickly built a 3500 foot

emergency runway and then began to expand it. About this time

the Fifth Air Force reevaluated their situation and decided to

move their base up to Nadzab and to make Gusap an advance base.

The road to Nadzab solved the supply problem from the port at

Lae. Gusap remained without a road connection.

As time went on the 312th

Bomb Group (A-20s) and the 41st

Fighter Squadron (P-47s) moved up to Gusap, as did two other

airborne engineer battalions (I think they were 872 and 873) The

runway was graded and stabilized with sprayed emulsion mix, taxiways

and hardstands were built and at least part of the runway was

covered with steel matting. The requirement to transport all

the materials by air limited what it was practical to do. We

built a tower and an operations building. The building was a

pre-fab unit made in Australia. The sections came folded up.

When erected, it had a metal roof, burlap and screen wire sidewalls

and a gravel floor.

Fuel for airplanes, and for everything else,

was shipped up in 55 gallon steel drums. The drums were recycled,

by welding, into culvert pipe needed for drainage. It rained

so much at Gusap! It was horrible. Your spare shoes would get

moldy. Everything got rusty. Your wash wouldn't dry. We were

there in the rainy season, I guess. The "other season" would

have to be the "wet season", and there is no "dry season".

At Gusap we were encouraged to hire native help.

The ANGAU (Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit) would arrange

for natives to assist us. The natives were thrilled because they

looked on the Americans as the friendly fatted cow. There was

a story that the Aussies would offer a cigarette for a certain

job, The American army would offer a couple of cigarettes. The

Air Corps would offer a pack and the Navy a carton and a T-shirt!

The natives mostly did manual labor like unloading planes and

cutting brush. There was also a native Papuan Infantry Battalion

who acted something like a native police force and tracking scouts

for the Aussies. They wore navy-blue uniforms that looked like

old wool bathing suits from the turn of the century. When

we were relieved at Gusap we were returned to Lae. At the port

area we got all our equipment together for the next move. I think

some of our companies went to either Finchhaven or Hollandia but

I was left behind again with a detail to clean up and ship out.

Owi Island

The next job that I remember was at Owi.

This is a coral island off of the coast of Biak The US 4lst Division landed on Biak but was met with strong resistance.

They needed air support. They couldn't control Mokmer strip so

we were sent to build another fighter strip on Owi that would

be able to cover at Biak. We loaded on to LSTs and were taken

to Owi. It proved to be solid coral and as hard as can be. The

airborne equipment just couldn't do very much. The D-4s were

only a little better. We hacked out the basic 3500 feet and were

soon reinforced and later relieved by a regular aviation engineer

battalion (864th?) and a Seabee battalion (60th?).

Owi also had little or no fresh water. The

natives wouldn't live there because there were chiggers that bit

you up and transmitted typhus. Later the Fifth Fighter Command

moved its HQ to Owi. We put up some prefab buildings. It was

there that I saw Charles Lindbergh. He was then a consultant

for Lockheed or Allison and was engaged to show the P-38 pilots

how to get better range. He was in one of the buildings we had

erected. He was signing autographs for some soldiers. In passing

the pencil, he dropped it and it rolled right along the floor

and out of "our" building. He laughed and asked who had built

this job! We said nothing.

The planes could take off at Owi, fly about four

or five miles, drop their load and return the four or five miles

back home. That was a "mission". We could see the bombs drop

and hear the explosions.

Sick Leave in Australia

While I was at Owi I contracted typhus fever.

So did many others. Previously, in New Guinea, most every one

seemed to have gotten dengue fever. We were all taking Atabrine.

We all had yellow colored skin. Sickness was quite a problem.

I was sent to a field hospital for treatment and, after recovering,

I was later sent back to Australia on sick leave.

I flew to Brisbane and then was sent to

Coolangatta (phonetic spelling). Coolangatta was about like Atlantic

Highlands NJ but at that time there was nothing to do but drink

beer and eat french fries. I remember that the bars had weird

hours, like 9-noon; then 1-4 and then closed for dinner. We had

trouble knowing the schedule. Food was very good, though, and

very cheap. A very nice breakfast of steak, eggs, tea and toast

served on a white table cloth with a linen serviette (napkin,

thank you) cost the equivalent of 32 cents US.

We had to be careful because not everyone appreciated

the Americans and their pay scale. Many Australian soldiers,

in Australia , resented us sometimes. On comparable ratings we

made as much in a week as they made in a month and we had been

saving it up for a long time.

Washing Machine Charlie

While I was away the 871st moved over to Biak.

We were at the north-most airfield. I think the name was Serrito

(phonetic spelling, While we were there we were drawing new heavy

equipment and we lost the designation of "Airborne". We got brand

new equipment from the states (like Christmas) and we started

to expand our roster to about 800 men.

At this stage of the war Japanese air power in

this area was through. At Tsilli-Tsilli it had been regular,

less at Nadzab and Gusap, and at Owi , even less. The Japanese

often did reconnaissance on us at night with a "washing machine

Charlie". On one occasion some of engineers were working with

flood lights on and failed to hear the air raid warning. They

didn't turn off the lights and they were saluted by the Japanese

with a stick of bombs. Some of our people were wounded but no

one was killed. They worked 24 hours a day. We had three line

companies and each worked an eight hour shift unless we were in

some emergency situation. In emergency situations they just worked

and worked.....and worked. No union rules here.

At Biak the bombers were flying very long missions,

sometimes 12-14 hours. A typical mission from Biak would happen like this. They

made incredible noise just warming up. The bombers (B-24s) would leave before

daylight, perhaps 4-5 am. By 6-7 am the fighters (P-38s) would follow them out

and catch up before the bombers got near their target. The fighters would be back

by 2-3 pm and the bombers an hour or so later. When the pilots had landed they

were so tired that their crew chiefs often parked their planes . There were

some accidents at landings, said to have happened because of the crews being over-tired.

They were flying missions to Borneo and later they were flying support mission

to the southern Philippines.

Philippines

We did not go to Leyte.

We were still being re-equipped and expanding at Biak. Our first

mission in the Philippines was the landing at Lingayen Gulf.

We got there about a week or so after the initial invasion. We

landed at San Fabian on Luzon. The beach head was still a mess

with equipment and supplies all over and just behind the beach.

We worked on a few "local" jobs, including some work at Dagupan.

Our first "move up" was to Clark Field for repairs to the landing

areas. This was a pre-war air base which had been lost in 1942.

The Japanese had used it until our re-invasion.

We, at first, had some trouble with un-exploded

munitions in the ground. These may have been planted as booby-traps

or they may have just been routinely unexploded bombs dropped

by both sides over time. Later, while we were creating

a borrow pit (for fill) the dozers unearthed trunks full of rifles

and bayonets. These were all well oiled and neatly preserved

and were probably buried to hide them from the Japanese. Some

of our men ground the US off of the bayonets and sold them to

the Navy and the merchant marine sailors as "genuine Japanese

" souvenirs.

Del

Carmen

Next we were sent to Del Carmen. This was

the "old name" that no one used in our time. Del Carmen was

a strip started by the 803 Aviation Engineers in 194l. Many of

them were lost after their capture , the Death March and years

in prison camps.

Del Carmen was a Spreckels "sugar central" located

near Florida Blanca and we always used "Florida Blanca" as our

location. We started to build an enormous runway and air field

installation there. All of our supplies had to be hauled by truck

from Manila 62 miles away. We were told that it was to be a B-29

base but after the successful invasion of Saipan and Okinawa it

was by-passed.

It was used later for B-32s which were similar

in size to the B-29s. The B-32s could reverse their props and

"back-up" into a hardstand. This feature fascinated us and everyone

would stop to watch!

It was used later for B-32s which were similar

in size to the B-29s. The B-32s could reverse their props and

"back-up" into a hardstand. This feature fascinated us and everyone

would stop to watch!

V-J Day

When the end of the war was announced I happened

to be in Manila. Every ship in the harbor fired their antiaircraft

guns in celebration. Of course what goes up must come down. It

rained shrapnel most of that night and we had to stay indoors

and under cover.

We came home on the "point" system. I went to

the 29th Replacement Depot and came back on a Liberty ship. We

had been overseas 2 years, 8 months and 20 days. I was discharged

on January 2, 1946 and was enrolled in college about a week or

so later. Total service - 3 years, 2 months and 27 days; in which

I "grew-up".

Postwar

Postwar

I attended SUNY Farmingdale

He then worked for New York State Department of .Agriculture and

Markets for 16 years. Then, for the State Fire Fighters Academy

of Fire Science. He retired at 55, as the Albany director of field

fire training.